Building Tone Ladder

The process of building Tone Ladder and how trying to make a half-formed idea real forced me to rethink the problem entirely.

Tone Ladder grew out of an idea I’ve had since art classes. Colours don’t get lighter and darker by adding white or black – they shift in hue relative to the colour of the light. A blue will shift towards green in warm sun; while shadows in the scene might tip towards a cool violet.

In digital design, we mostly ignore this. We think in terms of lightness alone – lighter colours go up, darker colours go down. We don’t “light” scenes at all. This approach is predictable and easy to systematise, but when we engineer predictability, we sacrifice richness.

Tone Ladder is an attempt to bring that painterly way of thinking into digital colour work.

My first attempt at the colour model behind Tone Ladder was a reproduction of my manual process. Take a colour, step lightness up or down, nudge based on temperature, and move on to the next step, and it felt like the right approach.

With the help of Claude Code (this was also a test of using AI to accelerate the development of a project like this, more on that in a future post) Version 1 came quickly, and although it had rough edges it was close to the picture in my head, it clearly showed the colour movement, with lightness and darkness ranges, and some of the hue variations were beautiful, but it also had some oddness – edge cases where hue would appear to go into another colour, or a lightness step that would feel like a huge jump relative to the rest of the ladder..

I set about testing: trying different colours and making notes, then feeding them into the algorithm as rules and tests, getting closer to the kinds of ladders I’d make by hand, but there were lots of rules building up.

Wrestling with Tone Ladder’s edge cases became exhausting, and I was getting nowhere addressing them one-by-one with special conditions.

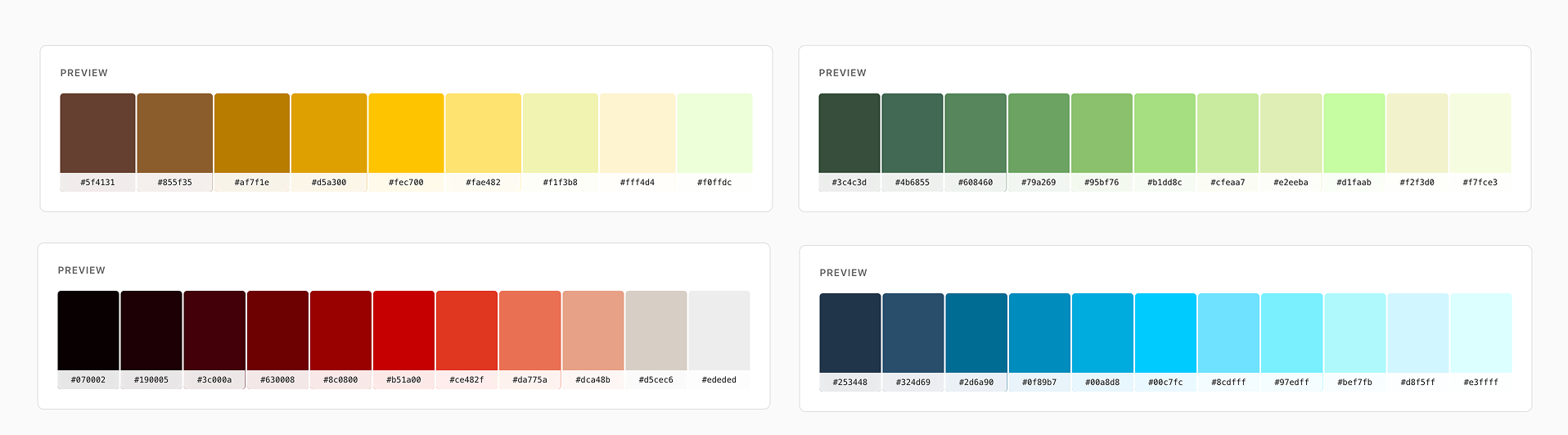

Early versions of Tone Ladder suffered from wobbly hues

The problem was that building a ladder as a sequence baked in and compounded errors. I’d chosen the wrong approach, but I didn’t have an answer for where to go next. So, I stepped away and looked outside the problem domain for answers.

Tone Ladder is a simulation of the real world. A rough approximation that tries to replicate the interaction of light, colour and surface. Something 3D rendering tools are good at.

I’d been close to this problem before, throwing a few hours at learning Blender for fun last year so I had a basic mental model of how this works in tools like Blender. You take a surface and you put a light on it, then you sample the colour at different points on the surface to get a ladder.

That led me to the realisation that a colour ladder isn’t a series of steps generated by an algorithm, it’s a continuous plane you sample at a pre-determined frequency.

This completely reframed the problem.

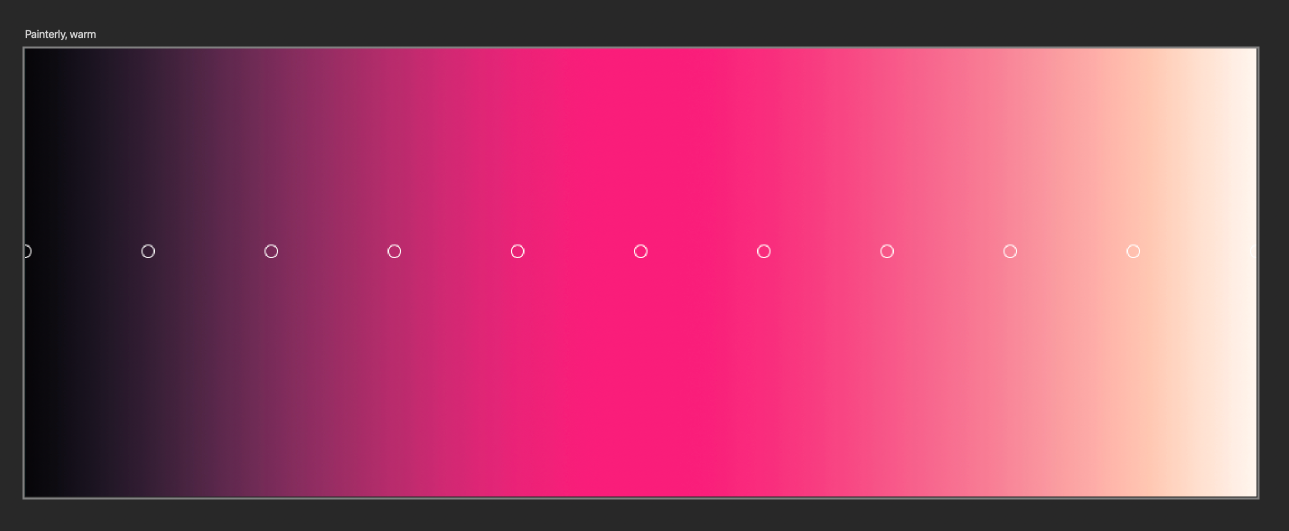

I built this as an experiment in Photoshop. A flat layer of base colour, two coloured gradients to simulate light temperature; one blue, one yellow, and one black to white gradient to simulate lightness changing. After some trial and error and fiddling with blending modes I had a model. From there I built sample ladders for different base colours in a few different light temperatures and configurations.

Building a ladder by hand in photoshop, with sample spots overlaid

Then I compared my manual ladders to what Tone Ladder was generating. Here’s what I observed.

lightness always increased steadily,

the midpoint was always the recognisable base colour,

steps felt evenly spaced perceptually, not numerically,

endpoints were rarely neutral under coloured light, and

weirdness happened, but it happened smoothly, not abruptly.

By stepping away from the tool and the problem space completely, then hand modelling and recording the outcomes I had described what Tone Ladder was trying to do. I had reverse-engineered a functional specification from a set of observations.

Turning those observations into constraints was enabling. I could change the algorithm completely, and as long as I stayed inside those boundaries I knew it was doing the right thing.

Where before we’d had a loop that jumped from colour to colour, and a testing process that was myself entering a colour, noting anything strange and tweaking the algorithm’s ruleset in response, we now had a behavioural contract.

The behavioural contract described what we wanted to observe from Tone Ladder, and outlined what was acceptable or unacceptable. This governed how Tone Ladder’s colours should look without specifying how, and Claude Code was free to move within the constraints.

Version 2 of the colour model moved away from the incorrect assumptions of the Version 1 and changed my role from tweaking and nudging outputs. With the support of a behavioural contract I could focus on getting the algorithm right.

Version 2 had three goals:

adopt the ‘generate a gradient and sample it’ metaphor,

give a clearer, more understandable role to the warm/cool light slider, and

deepen the gap between ‘conservative’ and ‘painterly’ modes.

I put Claude Code back to work, governed by the new behaviour contract and with a list of ‘golden tests’ to run after every iteration to prevent regressions (a huge headache in Version 1), and within a few hours the new colour model was ready.

The first time I used Version 2 I was underwhelmed. Everything looked ok, but we still saw edge cases: red would dip into mustard for example, or yellow would wander in and out of green, perceptual jumps weren’t quite right.

It wasn’t a fault in the algorithm though, it was mine. For safety I’d left the colour specific tests and tweaks per colour in the contract – and the old assumptions they were built on remained too.

Removing them had finally made the tool a working product.

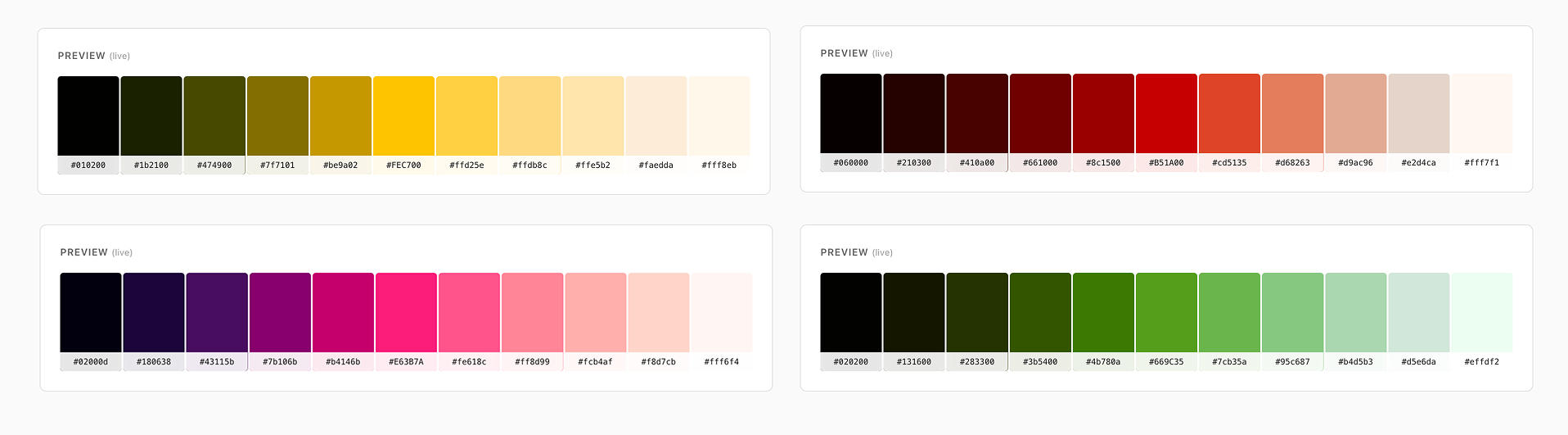

Tone Ladder’s hues are now much more stable, but allow you to push them much further for rich results

Version 2 was a far better reflection of my original vision, but only once I accepted the realities of colour perception and rendering. That acceptance shaped a better philosophy: committing to the concept, rather than smoothing away its consequences. If the theory is sound but the outcome feels uncomfortable, the controls are there to moderate it.

“That acceptance shaped a better philosophy: committing to the concept, rather than smoothing away its consequences”

Where I think Tone Ladder succeeds is a teaching tool – it demonstrates the concept in an interactive and experimental way. It invites you to play and learn the concept by doing.

I’ve started using it in my workflow, but it’s uncomfortable adopting a new tool for something I’ve been able to approximate myself well enough.

I could go farther with the UI, make it more intuitive, or I could look at turning into a Figma plugin, or open an API endpoint, all viable ideas and worth the work, but I think for now it’s time to get someone else’s eyes on it.

Tone Ladder was always an experiment. It scratched an itch I couldn’t shake, whether it succeeds beyond that I don’t know yet.

The role AI played in getting Tone Ladder built is another story… I’ll come back to that in a future post.